Imagine that you are trying to negotiate a pay raise with your boss. You might hesitate to make the first offer – let him toss a number out. But, research shows that the first one set the number is more likely to feel like the winner. It has everything to do with the anchor bias. Anchoring or focalism is a term used in psychology to describe the common human tendency to rely too heavily, or "anchor," on one trait or piece of information when making subsequent decisions. Numerical anchors are especially sticky in the brain.

For example, car salesmen often use anchors to negotiate prices. Instead of initially setting the price of a car at $25,000, they start at $27,000. That way, when the price comes down to $25,000 (the price they wanted all along), the customer perceives it to be a “better price.” The $27,000 price point is the anchor and anything below that feels like a deal.

Another anchor tactic is to show the consumer the most expensive items first. Imagine you walk into a dealership looking for a car in the $25,000 range, but the first car you see in the showroom is a luxury car priced at $50,000. The luxury car is obviously way too expensive, but the anchor is placed. The higher price point of the anchor will increase your willingness to pay because every other car will seem more reasonable in comparison. Conversely, if the dealer showed you the least expensive cars first, that lower anchor price reduces your willingness to pay anything higher.

J.C. Penney thought it was a smart idea to get rid of coupons. In 2012, Ron Johnson, the former head of Apple's retail stores and a Target executive who became the new JCPenney CEO, unveiled a sweeping overhaul of the chain. Central to the strategy was a plan to end coupons and discounts and replace them with low "everyday" prices.Too bad they didn’t know the power of psychological anchors. The plan backfired. Sales tanked nearly 25% and the company's stock plunged. Johnson was gone in 17 months.

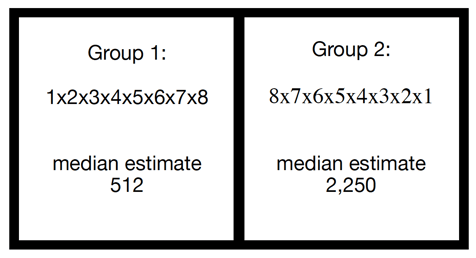

Anchoring, one of the most pervasive cognitive biases we experience, was first discovered by researchers, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who have studied it extensively. Back in 1974, Kahneman and Tversky conducted a study giving two groups of high school students a complex mathematical equation. They asked them to estimate the answer in 5 seconds.

Now, although the answer to both equations is 40,320, the groups gave different answers. Because of the limited time, participants quickly anchored to the product of the first few numbers of the mathematical expression which then influenced their estimates: a smaller number for an ascending sequence and a bigger answer for a descending sequence. Ultimately, this experiment proved that we subconsciously rely on the initial piece of information given even though it may result in an error in judgment.

Many studies have proven that we often become anchored by values that aren’t even relevant to the task at hand. In one study conducted by behavioral economist, Dan Ariely, people were asked for the last two digits of their social security number. Next, they were shown a number of different products, including things like computer equipment, bottles of wine, and boxes of chocolate and asked if they would be willing to pay the amount of money formed by their two digits. For example, if somebody’s number ended in 27, they would say whether or not they would pay $27 for each item. Even though a social security number has nothing to do with the value of the items, people who had higher digits were willing to pay significantly more for the same products compared to those with lower numbers.

“Social security numbers were the anchor in this experiment only because we requested them. We could have just as well asked for the current temperature or the manufacturer’s suggested retail price. Any question, in fact, would have created the anchor. Does that seem rational? Of course not.”

“Predictably Irrational” by Dan Ariely

In another experiment, a fair number of judges were asked how they would sentence a woman convicted of robbery. Before answering, loaded dice were thrown on the table so that the result was always going to be a 3 or a 9. The judges who got a 9 proposed an average sentence of 8 months in prison . The average sentence of the judges who got a 3 was only 5 months of prison.

Like most psychological phenomenon, anchoring can also be used for positive influences. The best example is 1975 study by Catalan, Lewis, Vincent and Wheeler. Researchers asked a group of students to volunteer as camp counselors two hours per week for two years. They all said no. The researchers followed up by asking if they would volunteer to supervise a single two-hour trip. Half said yes. They asked a second group to supervise a single two-hour trip without first asking for the two-year commitment. Only 17% agreed.

Since the anchoring effect occurs in so many situations, no single theory has fully explained it. Studies suggest that even when you know about anchoring and are forewarned, the effect can still affect your judgement. It just shows the power that the first piece of information has on how we make decisions in all facets of life.

Download this free whitepaper to learn more about

cognitive bias at work in the workplace.

Subscribe now to receive a Neuro Nugget delivered to your inbox!