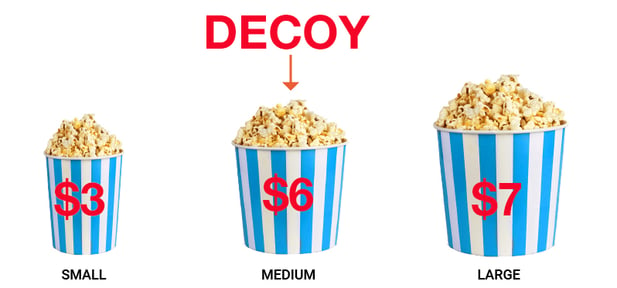

Imagine you go to the movies. As soon as you walk through the door, the aroma of buttered popcorn hijacks every ounce of willpower and before you know it you're standing at the snack counter. A small bag costs $3, a medium bag costs $6 and a large bag costs $7. That is a prime example of the decoy at work to nudge you to spend more.

How much we choose to spend or not spend on an item is one of the most important factors in the marketing mix. The decoy effect is one of the best known human biases violating rational choice theory that marketers use to get you to switch your choice from one option to a more expensive one. According to a large body of literature, we have a tendency to experience a specific change in preference between two options when also presented with a third option that is asymmetrically dominated (or the decoy) that, rationally, should have no influence on the decision-making process ...but it does.

In an ideal decoy situation, there are three choices available:

The target is the choice the seller wants you to make.

The competitor is the option competing with the target.

The decoy is the option that is added to nudge you towards the target.

The crux of the decoy effect is the fact that the decoy must be asymmetrically dominated by the target and the competitor, with respect to at least two properties—let’s call these A and B. This means that the target is rated better than the decoy on both A and B, while the competitor might be better on A but worse on B.

In the popcorn scenario, most customers evaluate their options based size and price. The large popcorn is the target (what the theater wants you to buy) and the small is the competitor. The medium popcorn is the decoy because it is asymmetrically dominated by the other two. Although it is bigger than the small, it is also twice as expensive, making it only partially superior. The large, however, contains more popcorn and is only slightly more expensive than the medium, making it a much better value.

National Geographic actually demonstrated the popcorn decoy in an informal experiment. When there were only 2 choices - small and large - very few purchased the large. But when the decoy medium was added, the large was overwhelmingly the most popular sale.

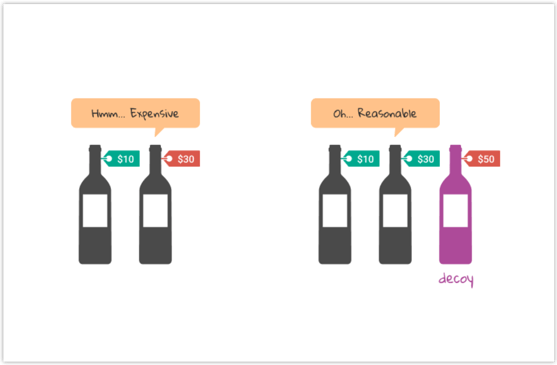

Consider another example. Imagine you're shopping for a bottle of wine. Compared to a $10 bottle, a $30 bottle might seem a little pricey. But throw in a decoy - a $50 bottle - and the $30 bottle seems a bit more reasonable.

Relativity is the key element in the decoy effect. Our brains aren't good at judging absolute values, but they are always comparing values and benefits. When used effectively in marketing, a decoy product can make another product look like a better value.

The decoy effect can influence us in countless areas of our lives - even in politics. Some believe that Independent candidate Ralph Nader was a powerful decoy in the 2000 US Presidential election between front runners Al Gore and George W. Bush. Rather than take votes away from Gore, psychologists maintain that Nader actually increased the number of votes cast for the candidate he more closely resembled: George W. Bush.

Decoys work because of the weaknesses in our decision making processes. As amazing as the human brain is, we default to intuition over logic and . Decoys make it easy to rationalize our intuitive choices and prey upon our dislike of losing out on a better deal.

The Bottom Line:

When we make decisions, the goal is not to pick the best choice;

the goal is to justify the choice we've already subconsciously made.